Hot Versus Cold

So far, we have considered that all Flux (and Mono) are the same: They all represent

an asynchronous sequence of data, and nothing happens before you subscribe.

Really, though, there are two broad families of publishers: hot and cold.

The earlier description applies to the cold family of publishers. They generate data anew for each subscription. If no subscription is created, data never gets generated.

Think of an HTTP request: Each new subscriber triggers an HTTP call, but no call is made if no one is interested in the result.

Hot publishers, on the other hand, do not depend on any number of subscribers. They

might start publishing data right away and would continue doing so whenever a new

Subscriber comes in (in which case, the subscriber would see only new elements emitted

after it subscribed). For hot publishers, something does indeed happen before you

subscribe.

One example of the few hot operators in Reactor is just: It directly captures the value

at assembly time and replays it to anybody subscribing to it later. To re-use the HTTP

call analogy, if the captured data is the result of an HTTP call, then only one network

call is made, when instantiating just.

To transform just into a cold publisher, you can use defer. It defers the HTTP

request in our example to subscription time (and would result in a separate network call

for each new subscription).

On the opposite, share() and replay(…) can be used to turn a cold publisher into

a hot one (at least once a first subscription has happened). Both of these also have

Sinks.Many equivalents in the Sinks class, which allow programmatically

feeding the sequence.

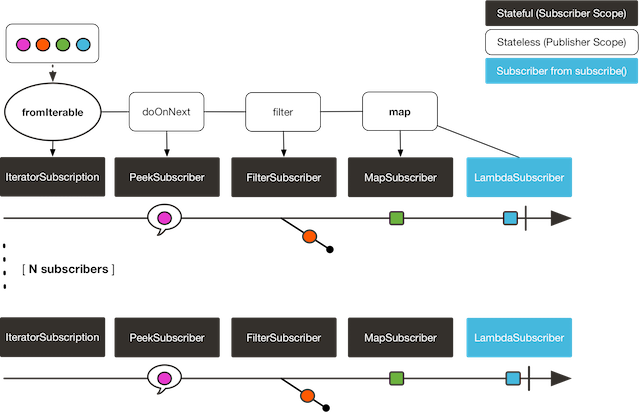

Consider two examples, one that demonstrates a cold Flux and the other that makes use of the

Sinks to simulate a hot Flux. The following code shows the first example:

Flux<String> source = Flux.fromIterable(Arrays.asList("blue", "green", "orange", "purple"))

.map(String::toUpperCase);

source.subscribe(d -> System.out.println("Subscriber 1: "+d));

source.subscribe(d -> System.out.println("Subscriber 2: "+d));This first example produces the following output:

Subscriber 1: BLUE

Subscriber 1: GREEN

Subscriber 1: ORANGE

Subscriber 1: PURPLE

Subscriber 2: BLUE

Subscriber 2: GREEN

Subscriber 2: ORANGE

Subscriber 2: PURPLEThe following image shows the replay behavior:

Both subscribers catch all four colors, because each subscriber causes the

process defined by the operators on the Flux to run.

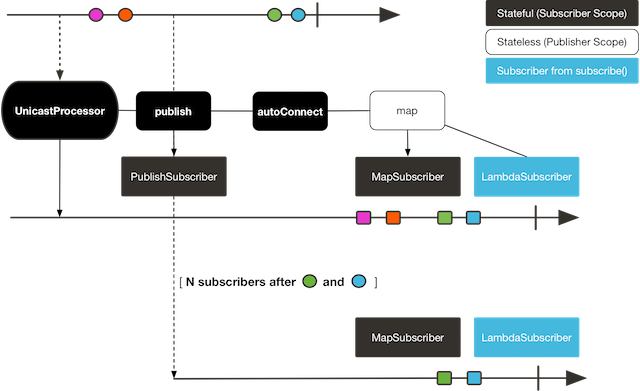

Compare the first example to the second example, shown in the following code:

Sinks.Many<String> hotSource = Sinks.unsafe().many().multicast().directBestEffort();

Flux<String> hotFlux = hotSource.asFlux().map(String::toUpperCase);

hotFlux.subscribe(d -> System.out.println("Subscriber 1 to Hot Source: "+d));

hotSource.emitNext("blue", FAIL_FAST); (1)

hotSource.tryEmitNext("green").orThrow(); (2)

hotFlux.subscribe(d -> System.out.println("Subscriber 2 to Hot Source: "+d));

hotSource.emitNext("orange", FAIL_FAST);

hotSource.emitNext("purple", FAIL_FAST);

hotSource.emitComplete(FAIL_FAST);| 1 | for more details about sinks, see Sinks |

| 2 | side note: orThrow() here is an alternative to emitNext + Sinks.EmitFailureHandler.FAIL_FAST

that is suitable for tests, since throwing there is acceptable (more so than in reactive

applications). |

The second example produces the following output:

Subscriber 1 to Hot Source: BLUE

Subscriber 1 to Hot Source: GREEN

Subscriber 1 to Hot Source: ORANGE

Subscriber 2 to Hot Source: ORANGE

Subscriber 1 to Hot Source: PURPLE

Subscriber 2 to Hot Source: PURPLEThe following image shows how a subscription is broadcast:

Subscriber 1 catches all four colors. Subscriber 2, having been created after the first

two colors were produced, catches only the last two colors. This difference accounts for

the doubling of ORANGE and PURPLE in the output. The process described by the

operators on this Flux runs regardless of when subscriptions have been attached.